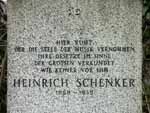

Heinrich Schenker

(1868–1935)

In the realm of tonal music, Heinrich Schenker was the most penetratingly original thinker of the 20th century. His way of hearing music, developed over a forty-five year career, was embodied in a formalized theory and expressed through a sophisticated method of music analysis by way of treatises, monographs, articles, periodicals, and editions that have had an irrevocable influence on the way the world thinks about music. He was first and foremost a musician. A pianist with professional experience, possessing an exceptionally acute ear, he was a musician's theorist, a musician's analyst: never concerned with dry mechanisms, Schenker worked always with the impact of music on the ear and its effect on the human mind. Moreover, his theory and method have been adopted by those examining medieval and renaissance music, and even music that Schenker himself scorned: impressionist and atonal music, jazz, popular music, and music of non-western traditions.

Early Life : 1868–1901

Schenker was born on June 19, 1868 in Wisniowczyk (in Galicia), of a Jewish family. At least two years younger than his educational cohort, he attended Polish-language schools, first in Lemberg (now L'viv, grades 5-8) – in addition studying piano with Karl Mikuli, an erstwhile pupil of Chopin – then in Brzežany (grades 9-12). The curricula were rigorous in history, social science, and especially in classical languages (Latin, Greek), but also required study of Polish and, in the upper grades, German and its literature for students of German-speaking households. In 1884, at age 16, Schenker graduated first in a class of 35. His elder brother Wilhelm had graduated the same high school a year earlier.

Schenker moved to Vienna in 1884, where he studied law at the University of Vienna from that year to 1888. He took a comprehensive curriculum of over thirty courses, including jurisprudence, legal history, and methodology, earning his doctorate in 1890. Echoes of Schenker's legal education resonate in his analytic approach to music. He emerged with a legal cast of mind reflected in his juridification and moralization of music as the "life of the tones." Schenker's teachers included Georg Jellinek, whose reconciliation of order with liberty foreshadows Schenker's synthesis of harmonic structure with contrapuntal freedom via prolongation, and Robert Zimmermann, whose rational ethical aesthetics foreshadow Schenker's equation of truth, beauty, and righteousness. Schenker’s laws of music adjudicate the juristic dialectic between authority and autonomy in a hierarchical community of tones embodied in his motto semper idem sed non eodem modo ("always the same, but not in the same way"). From 1887 to 1890 he was concurrently enrolled at the Vienna Conservatory of Music, studying harmony and counterpoint with Anton Bruckner, piano with Ernst Ludwig, and composition with Johann Nepomuk Fuchs.

His father, a country doctor, died at the end of 1887, and in order to support his family Heinrich embarked on the activity that would frame his entire career: private piano teaching at home. Further income came from work as a music critic between 1891 and 1901 for newpapers and journals in Vienna, Leipzig, and Berlin. But during this time, Schenker saw himself primarily as a composer and pianist, publishing small-scale compositions, which received performances between 1892 and 1903, and remaining active as an accompanist and conductor.

Theorist and Editor: the First Period : 1901–1911

For Universal Edition, newly founded in Vienna in 1901, Schenker edited selected keyboard works by C. P. E. Bach (1903) and later J. S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy & Fugue (1910). These editions marked the beginning of a life-long involvement with composers' autograph manuscripts, copies, and early printed sources, the contents of which he sought to transmit without editorial intervention, save for footnoted commentary.

For the C. P. E. Bach edition he provided a companion guide to executing the ornamentation, but with significant remarks on form and compositional process: Ein Beitrag zur Ornamentik (1903). This was based in part on Bach's own treatise, Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (1753, 1762), a work that was to permeate Schenker's whole conceptual world as a theorist. Within the J. S. Bach edition he supplied a detailed commentary termed "Erläuterungen" (elucidations): this volume inaugurated a series of “Erläuterungsausgaben” by Universal Edition.

The series on which Schenker's fame today largely rests, Neue Musikalische Theorien und Phantasien (New Musical Theories and Fantasies), had its origins in an essay started in 1903 entitled "Das Tonsystem," which evolved into the opening sections of his Harmonielehre (J. G. Cotta, 1906), in which work he expounded the central concepts of Stufe (harmonic scale-degree) and Auskomponierung (literally "composing-out," i.e. elaboration), along with tonicization and chromaticization. It was in Decline of the Art of Composition, planned as an afterword to Harmonielehre, revised 1905–09 as a separate volume in the series but ultimately unpublished, that Schenker first articulated his enduring polemic against the 19th century (especially Berlioz and Wagner) for sweeping aside the "immutable laws" of composition embodied in German composers of the classical period, whose mastery of cyclic forms found continuity in the music of Mendelssohn and, finally, Brahms.

The second volume of the series, Kontrapunkt, was originally planned as a single volume, but split in order to facilitate publication of the first half-volume ("Cantus Firmus and Two-voice Counterpoint") in 1910 (Cotta), the second ("Counterpoint in Three and more Voices; Bridges to Free Composition") being delayed by the war and eventually published in 1922 (UE). While Schenker's exposition of the five species of counterpoint from two to eight voices was based on that of Fux and his successors, it was unique in considering the combining of tones in terms of the "affects" that they produced, rather than mechanical formulations, and for demonstrating how Fuxian counterpoint underpinned real pieces of music. Harmonielehre and Kontrapunkt had in common that they adopted a "psychological" point of view. Neither was a textbook in the normal sense; each was more a training in how to hear music properly. (Indeed, the original working title for the latter was "Psychologie des Kontrapunkts.")

In 1908, Schenker published with UE the work that sold more copies than any other of his works, the Instrumentations-Tabelle, under the pseudonym of Artur Niloff: a wall-chart of musical instruments, showing for each the fundamental, overtones, range, special features, with a picture and repertory list. Around this time he also mapped out a theory of musical form (1907) and he made a first draft of a book entitled Die Kunst des Vortrags (The Art of Performance, 1911); he returned to both from time to time, intending quite late in life to finalize them, but neither was published.

Between 1901 and 1910, Schenker established working relationships with his two principal publishers: UE and J. G. Cotta of Stuttgart. Begun harmoniously, both relationships were at times troubled. That with UE became stormy within a year of Emil Hertzka's taking up its directorship in 1907, and those troubles would recur in ever-mounting waves, alternating with periods of relative calm, until a breaking point was reached in 1925. The relationship between the two men was complex, admiration and respect mingled with suspicion and exasperation. In his personal life, Schenker became acquainted with Jeaneth Kornfeld, wife of his friend Emil Kornfeld, around 1903. A relationship developed over seven years, and in 1910 she left her husband to devote herself to helping Schenker in his work. By late in 1911, she was taking down his extensive diaries in shorthand, and by 1912 his lesson notes, writing up fair copies of both in exercise books. She also took letters and wrote up drafts for Heinrich to correct and write fair copies.

Theorist and Editor: the Middle Years : 1912–25

Work on the first half-volume of Kontrapunkt and his J. S. Bach edition complete, by June 1910 Schenker's mind turned toward an analytical study of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. At that time, Decline of the Art of Composition was envisioned as volume III of Neue Musikalische Theorien und Phantasies, and Schenker planned a Handbibliothek (pocket library) of short guides to individual works as an "appendix" to that volume, to be published by Cotta and inaugurated by a study of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Each was to comprise a score plus "Erläuterungen," and this format was by 1913 embodied in the composite term "Erläuterungsausgabe" (elucidatory edition). The handbook on the Ninth Symphony grew in size, and was published in 1912 by UE as an independent monograph, without accompanying score; nevertheless, it established the format for the future: analytical commentary—performance —survey of secondary literature.

The notebooks in which Schenker recorded the details of each lesson given in his private piano studio survive from 1912 onwards, and these in conjunction with his diaries afford a sense of what his life was like during the academic "season," October to June. He taught Monday to Saturday inclusive, each lesson of one hour. Students usually attended twice or three times a week, other students coming once a week, a few on an occasional basis. Serious students took not only piano technique and interpretation but also at least a year of counterpoint, a year of thoroughbass, and a year of chorale writing, plus source studies and editorial technique, and analytical method. It was a fully integrated music education, unique in its time, designed to train up a new generation of musicians for all walks of musical life in a mode of thought wholly new yet deeply rooted in tradition.

On a typical full day, rising early Schenker worked on his publications until 11 am, taught 11–1 pm, then with Jeanette went to a local restaurant or coffee house for the day's main meal; thereafter lessons 2–4, a teatime break (Jause), perhaps a short walk, then a further lesson. The evening might involve a concert, receiving or visiting friends, otherwise an evening meal at home followed by further study, including dictation to Jeanette, whose work might then go on into the early hours of the morning while he himself also worked late. July to mid-September was spent in the mountains of the Tyrol or the Salzkammergut, reading, hiking, playing piano, doing conceptual groundwork for future publications, correcting proofs and, on occasion, receiving visits from his keenest pupils.

Schenker's next major undertaking concerned the last five Beethoven piano sonatas, Opp. 101, 106, 109, 110, and 111, for each of which he planned a single volume containing a Foreword, the complete score, a "Preliminary Remark to the Introduction," the "Introduction" itself (analysis, textual commentary, and performance), and "Secondary Literature" (NB the 1971–72 re-editions are heavily abridged, and in the 2015 translation, which is complete, the secondary literature material is accessible only on the web). That for Op. 106 was never produced, because the autograph manuscript could not be found. The remainder of the series, entitled Die letzten fünf Sonaten von Beethoven, was published in 1913, 1914, 1915, then 1920. Working much of the time under wartime conditions, Schenker consulted autograph and printed sources, and notes by Nottebohm, available in Vienna, and obtained photographs of sources from libraries and collectors in Germany and elsewhere, meticulously collating his sources to determine Beethoven's ultimate intentions. Schenker's antagonism toward what he dubs "hermeneuticist" analysts is at its strongest in these texts, as is his campaign against misguided editors. The delaying of Op. 101 was propitious in that Schenker had meanwhile developed his concept of Urlinie (fundamental line) and could deploy it publicly for the first time in that volume, using a modified form of standard musical notation with small and large stemmed and unstemmed noteheads, horizontal brackets and slurs, combined with thoroughbass figurings.

His work on the last five sonatas then led to his producing UE's new edition of the complete Beethoven sonatas between 1921 and 1923, each edited according to the early sources. He also produced a facsimile edition of the "Moonlight" Sonata in 1921 for series edited by Otto Erich Deutsch.

Schenker continued to develop his "pocket library" plan throughout the 1910s, renaming it Kleine Bibliothek (Little Library); but by the time it began publication it had mutated into a periodical, Der Tonwille, each of its ten outwardly modest issues offering a fiery admixture of theoretical articles, work analyses, and miscellaneous comment. In practice, the first issue was released within a few days of the Op. 101 in summer 1921, so that the latter's Urlinie graphs complemented nicely the former's important article "The Urlinie: a Preliminary Remark." Tonwille saw the gradual extension of these graphic devices into a highly sophisticated system. It also contains some of Schenker's most important studies of large-scale works, notably that of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony (issued as a separate volume in 1925), and a series of short analyses, of which those devoted to Bach’s short keyboard preludes have had a wide pedagogical influence, and the term "Ursatz" (literally primal counterpoint) was introduced at first isolatedly in issue 5 (1923). Schenker's reaction to World War I, which had seeped into the late Beethoven sonata volumes, surfaced violently in the first issue in his most polemical essay, "The Mission of German Genius," with its reaction to the Versailles Treaty and its diatribes against the romance and anglo-saxon nations and the world of commerce, and his condemnation of what he saw as the artistic mediocrity of his day. The political content of Tonwille led Emil Hertzka to suppress some of Schenker's material, and a slow build-up of animosity led to impending court proceedings, an out-of-court settlement in December 1925, and a severing of all communications.

Between 1910 and 1919, Jeanette Kornfeld's petitions for a separation from her husband (to which Heinrich brought his legal training to bear) met with solid resistance from her husband and his lawyers. Only after the country's marriage laws had been changed was a divorce finally granted, and Heinrich and Jeanette were permitted to marry, on November 10, 1919. Even so, it was not until November 1921 that they were able to unite their two households in an apartment on the Keilgasse, Vienna III. Meanwhile, in 1914 Schenker had been diagnosed with diabetes, a condition that affected his day-to-day life and, ultimately, would claim it.

Theorist and Editor: the Mature Years : 1926–35

Already by the break with UE in 1925, Schenker had identified an alternative publisher, Drei Masken Verlag of Munich, which refused to continue the existing periodical and insisted on a new identity as Das Meisterwerk in der Musik, and publication as a "yearbook" (Jahrbuch), each commensurate with the last four issues of Tonwille. Three yearbooks were produced, dated 1925, 1926, and 1930, all modeled on a typical issue of Tonwille, with theoretical articles, analyses, and miscellany, but with the political polemic subdued. Meisterwerk 1 most closely resembles the Tonwille pamphlets, being made up of twelve essays of varying lengths; here the concept of Ursatz was now well defined, and many other mature concepts, such as arpeggiation (Brechung), linear progression (Zug) registral transfer (Höher- and Tieferlegung), and reaching-over (Übergreifen), were widely deployed. Meisterwerk 2 and Meisterwerk 3 contain fewer, longer items, each offering one major analytical article on a four-movement work: Mozart's Symphony No. 40, in G minor, and Beethoven's "Eroica" Symphony, respectively, each retaining some vestiges of the earlier Erläuterungsausgabe format. These two analyses reveal the confidence with which Schenker now operated in the analytical mode, and serve as the two most important full-length exemplars of his method. The graphic techniques begun in Op. 101 now reached maturity in graphs printed on large, separate sheets of paper (exquisitely engraved by Waldheim-Eberle of Vienna) displaying parallel horizontal layers using extended multi-level beams and slurs to convey long-term time-spans and tonal coherence, and dotted lines and slurs, special symbols and abbreviations to show voice-leading and interaction between voices, inter-relations between tones, and chordal function.

November 1928 saw a tentative resumption of communications between Schenker and Hertzka. In 1932, Schenker described how, after completion of the "Eroica" Symphony graphs in Meisterwerk 3, the "presentation in graphic form" had been "developed to a point that makes an explanatory text unnecessary." From fall 1931, Schenker conducted a seminar with four of his students, each student assigned a composition on which to work, and from that seminar emerged his Fünf Urlinie-Tafeln / Five Analyses in Sketchform, published by the David Mannes Music School, New York (where his pupil Hans Weisse was teaching), but engraved by Waldheim-Eberle with UE as the European distributor. The works graphed were a J. S. Bach chorale, the first prelude of the Well-tempered Clavier Book I, a section of a Haydn sonata movement, and two Chopin Etudes. (A second volume was mooted but never materialized.)

Schenker's work with photostat copies of sources prompted him to propose the establishment of an archive of copies of "musical master manuscripts," available for consultation by scholars. This took shape in 1927 as the Photogrammarchiv, located in the Austrian National Library, with Schenker's pupil Anthony van Hoboken as its archivist. By 1934, it already held over 30,000 pages, and it continued to grow thereafter. In the Archive of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna there was a Brahms autograph manuscript that bore testimony to the composer’s interest in contrapuntal technique and wide knowledge of the musical respertory and history of theory, which recorded 140 instances of parallel fifths and octaves in music from the mid-16th to the mid-19th century; some Brahms regarded as unacceptable, others as tolerable, others as entirely acceptable. For many years, Schenker had had his students study this manuscript, and in 1933 to mark the centenary of Brahms's birth he published a facsimile of this eleven-page source with commentary.

By the early 1930s, Schenker could rightly claim that his theories were being disseminated within Europe by his students and disciples to their pupils. Such were Moriz Violin and Felix-Eberhard von Cube in Hamburg, Otto Vrieslander in Munich, and Reinhard Oppel at the prestigious Leipzig Conservatory. Schenker took particular pride in the influence that his ideas had on Wilhelm Furtwängler, hence on the latter's interpretations of works in the concert hall. The first to teach his theories in a foreign language (and to quote him in an English publication) was John Petrie Dunn at the University of Edinburgh, until his tragic death in a road accident in 1931; the American organist Victor Vaughn Lytle, who had studied with Hans Weisse in the late 1920s, took a theory teaching post at Oberlin College, Ohio. In September 1931, Weisse left Vienna to take up an appointment as theory and composition teacher at the David Mannes Music School and Columbia University in New York City in September 1931, where he attracted a wide circle of admiring pupils and laid the foundations of American Schenker pedagogy.

The second half-volume of Kontrapunkt, which had been published in 1922, concluded with the "Bridges to Free Composition." Even as late as 1920, however, Kontrapunkt had been intended to include a section on free composition, already drafted by summer 1917. However, 1917–20 being so conceptually fertile a period, in which Urlinie and Ursatz were adumbrated, and his subsequent redactions to this section being so extensive, Schenker decided to abandon its inclusion in volume II/2 and envisioned a volume II/3 of Neue musikalische Theorien und Phantasien entitled Freier Satz. But by 1925, after publication of Op. 101 and the issues of Tonwille, and with work on Meisterwerk 1, Schenker had reconceived this as volume III of the series, with the slightly modified title of Der freie Satz. For the next ten years he worked on what became the summation of his mature theory, cast into three main parts, "Background," "Middleground," and "Foreground," each explicated systematically (as in volumes I and II) in sections, chapters, and numbered paragraphs in the manner of an 18th-century treatise. The "elemental driving force" (Urkraft) of the entire edifice was the Ursatz—in which Urlinie and Bassbrechung (bass arpeggiation) unite in counterpoint, representing respectively horizontal and vertical forces, falling and rising lines, and embodying the first tones of the harmonic spectrum. To the text, Schenker provided a companion volume of musical graphs. Schenker died on January 14, 1935, not having corrected the proofs of Der freie Satz; this was seen through the press by his widow and others.

Schenker's Legacy

Already in January 1930, the rise of the National Socialists in Germany had cast its shadow on Schenker's life, putting beyond reach a prospective official appointment in Berlin. Soon after his death, his students, his living legacy, most of whom were Jewish, were scattered: many emigrated to the USA and elsewhere, others remained and were deported (as was his own wife) to the camps. The Schenker Institute established in Vienna a few months after his death was closed down in 1938, as had been a similar institute in Hamburg in 1934. Copies of his publications at UE were confiscated by the Gestapo, and he himself was characterized grotesquely in the Lexikon der Juden in der Musik as "Chief representative of the abstract music theory of Jewish philosophy that disavows the existence of a spiritual content in music and limits itself to constructing tone rows from the correlation of individual sonata movements in arbitrary combination, from which an 'Urlinie' is read." The dissemination of his ideas was to come not from Europe but from the USA, through his students Hans Weisse, Oswald Jonas, and Felix Salzer, and through their students. The influence of Schenker's theories blossomed there in the 1950s and 1960s, and gradually extended back to Europe and to other parts of the world during the later 20th century.

Contributors:

- Ian Bent, with William Drabkin, Wayne Alpern, and Lee Rothfarb