Browse by

OJ 5/7a, [46] (formerly vC 46) - Handwritten letter from Schenker to Cube, dated May 14, 1933

|

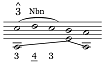

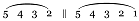

Alles im Briefe= OJ 9/34, [37], Ausführungen, Bekenntnis zeigt ein ungewöhnliches Maß von Können u. Charakter, wie es nur ganz wenige mit Ihnen heute teilen. Sagte ich, schrieb ich Ihnen das schon öfter, so wiederhole ich auch noch dieses: wenn Jemand, wie Sie, solchen Grad von „Abhorchen“ u. Darstellung zeigt, hat sozusagen das Recht auch auf einen gelegentlichen Irrtum: ein Irrtum auf der Base der Wahrheit ist noch immer wertvoller als ein Irrtum auf einer Base, die selber ein Irrtum ist. Wie leicht könnte es Ihnen widerfahren, was auch mir so oft widerfahren ist, daß Sie, nach Monaten, nach Jahren plötzlich den Blick ganz frei bekommen auch für Dinge, die Sie, durch Tumult des Tages, Mißstimmung, Hast (!), abgezogen zunächst wenig beachtet haben. Übrigens ist die Frage Ą oder Ć, Ć oder ĉ, u dgl. ĉ oder Ą eben die Tonraum-Frage, ob 3, ob 5, ob 8, die zu enscheiden wohl als Schwierigste gelten mag. Nun zur Sache: 1) Der strenge Satz (vgl. II1

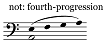

, 2. u. 3. Gattung) lehrt, daß die

Nbn genau so frei eintritt, wie der Bruder

Durchgang

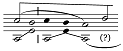

2) Dazu kommt eine Unwägbarkeit:

3) Über die Auskomp. T. 5–8 s. „Erläuterungen“, Jb I 203, fig 4 c, die letzten 3

Beispiele,

3

u. Tw.

2

Moz.

Son. am. letzter

Satz, T. 5–8,

4

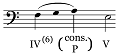

usw. Der zur der einer solchen Auskomp. zugeteilte Baß Kp. dient

nur ihr

†

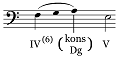

, gleichviel ob er auf den „kons. Dg“ von

oben (Sext) oder von unten (Terz) zugeht. Also ist es unstatthaft,

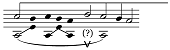

{3} so zu lesen:

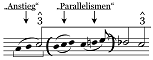

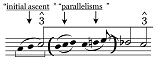

4) Es geht nicht an, aus der Auskomp:

5) T. 21–22 bringen eine Abkürzung von T. 5–8

{4} Endlich zu Ihrem schönen dritten Blatt! Das geschichtliche Verdienst Hitlers, den Marxismus aus zugerotte nt zu haben, wird die Nachwelt (einschließlich der Franzosen, Engländer, u. all der Nutznießer der Verbrechen an Deutschland) nicht weniger dankbar feiern, als die Großtaten der größten Deutschen! Wäre nur der Musik der Mann geboren, der die Musikmarxisten ähnlich ausrottet: dazu gehörte vor Allem, daß sich die Massen dieser in sich versponnenen Kunst näherten, was aber eine – contradictio [corr] in adjecto ist u. bleiben muß. „Kunst“ und Massen haben nie zusammengehört, werden nie zusammengehören. Woher nun aber die Quantitäten der Musik-„Braunhemden“ nehmen, mit denen es gelingen müsste, die Musikmarxisten hinauszujagen? Die Waffen habe ich bereitsgestellt, aber die Musik, die wahre deutsche der Großen, findet kein Verständnis bei den Massen, die die Waffen tragen sollten. Fast habe ich den Eindruck, als nähmen Sie an, ich sei von dem Weltumlauf unberührt. Ich habe sehr schmerzliche 3 Jahre hinter mir, voll Sorgen um die Kunst, um uns Beide, um die Mitwelt. Die Sorgen haben meinen Körper stark in Mitleidenschaft gezogen u. wiederum ist die {5} Einsamkeit unserer großen Musik die Ursache, weshalb auch ihre Priester mitgerissen werden. Woher sollte den Menschen auch nur Mitleiden kommen, wenn sie wirklichen Musikern begegnen, wenn da sie schon an der Musik keinerlei Interresse empfinden?! Die Priester werden so selber zum Got Opfer der Göttin! Violins’ Lage ist mir, ohne daß er es wußte, von Zeit u. [sic] Zeit durch seine Schwester bekannt gemacht worden, sie erzählte schaudervolle Sachen! Er schwieg, erst jetzt gestand er seine übergroße Nervosität ein. Doch wußte auch seine Schwester sehr wenig, – das Wenige

war erschütternd traurig – so daß ich über seinen Schritt

5

zu urteilen mir versagen muß. Vielleicht war Niemand so fern seiner Lage, wie ich. Was er

Ihnen {6} seinerzeit versprochen, dann, wie ich höre, leider nicht gehalten hat, ist mir bis zur

Stunde verborgen. Auf die Übersiedlung habe ich keinerlei Einfluß genommen, wie hätte ich es dürfen, wenn ich

ihm nicht einmal in seinen ärgsten Nöten beispringen konnte! Er hat mir 2 Schüler angekündigt u. die Honorare

selbst – in Kenntnis der Sachlage – ausgemacht. (Ich hätte es nicht getroffen.) Aber, wenn die reichsten Schüler

finanziell zusammenbrechen, {7} Sie sehen, wie schwer sich auch bei mir das Leben inzwischen gestaltet hat, wie doch bei fast allen Musikern allüberall. Der Weg zur Genesung, der künstlerischen wie materiellen, kann nur über meine Lehre führen, gerade aber diese fällt den Leuten genau so schwer, wie die Meisterwerke selbst. Von Dr Jonas kommt das Buch 6 dann doch im Herbst heraus. Prof. Oppel leitet in Leipzig – er ist Hauptmann mit Eisernem Kreuz gerufen! – eine national-soz. „Zelle“, in der er nach wie fort vor nach Tunlichkeit Schenker weitergibt. 8 {8} Hat Ihnen Furtwängler geantwortet? 9 © Transcription William Drabkin, 2008 |

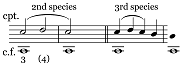

Everything in your letter= OJ 9/34, [37] – your arguments, your declaration – shows an extraordinary measure of capability and character, which very few people today share with you. If I have already told you, written to you that many times, let me also reiterate the following: anyone who, like yourself, has demonstrated such a degree of "attention" and presentation has, so to speak, the right to make an occasional mistake: a mistake made on the basis of the truth is always more valuable than a mistake made on a basis that is itself a mistake. How easily it could befall you, as it so often befalls me, that things to which you had paid too little attention – and had remained concealed by the hectic pace of daily life, by feelings of depression, or by doing things in a rush (!) – all of a sudden become crystal clear. Moreover, the question of Ą or Ć, Ć or ĉ, and the like ĉ or Ą is that very question about tonal space, whether 3 or 5 or 8, that is perhaps the most difficult to decide. Now to the matter itself: 1) Strict counterpoint (see

Counterpoint, vol. 1, chapters on the second and third

species) teaches us that the neighbor note may be introduced just as

easily as her brother, the passing note:

2) To this an imponderable is added:

3) Regarding the elaboration, mm. 5–8, see "Elucidations,"

Yearbook, vol. 1, p. 203,

Fig. 4c, last three illustrations,

3

and Mozart's Sonata in A minor, last movement, mm. 5–8, in

Der Tonwille, vol.

2.

4

The bass

counterpoint assigned to such an elaboration serves only that elaboration

†

, regardless of whether the

"consonant passing tone" is approached from the sixth above or the

third below. Thus the following {3} reading is incorrect:

4) It is not permissible, given the following elaboration:

5) Measures 21–22 represent an abbreviation of measures 5–8

{4} Finally, your beautiful third page! Hitler's historical service, of having got rid of Marxism, is something that posterity (including the French, English, and all those who have profited from transgressing against Germany) will celebrate with no less gratitude than the great deeds of the greatest Germans! If only the man were born to music who would similarly get rid of the musical Marxists; that would require that the masses were more in touch with our intrinsically eccentric art, which is something that, however, is and must remain a contradiction in terms. "Art" and "the masses" have never belonged together and never will belong together. And where would one find the huge numbers of musical "brownshirts" that would be needed to hunt down the musical Marxists? I have prepared the weapons, but the music – the true German music of the greats – finds no understanding among the masses who should bear the weapons. I almost have the impression that you believe I am untouched by the course of the world. I have endured three painful years, full of troubled thoughts for art, for the two of us [myself and my wife], for my friends. These thoughts have affected me physically, and the {5} isolation of our great music is once again the cause, for which reason its priests are dragged along. How can one expect people to feel empathy, if they encounter true musicians, if since they already feel no interest in music in the slightest. The priests will thus themselves become a sacrificial offering to the goddess! I have been informed of Violin's situation from time to time by his sister, without his knowing it; she recounted terrifying things! He was silent, and only now did he admit the extent of his nervous condition. Yet even his sister knew very little – the little that

she knew was distressingly sad – so that I had to refrain from making a judgment about the steps he

took.

5

Perhaps no one was more ignorant of his situation than I

myself. What he promised you, {6} for his part, but then – so I hear – failed to make good, has to

this time been unknown to me. Regarding his move, I exerted no influence whatever; how could I have done so if I

was unable to rush to help him in his hour of greatest need? He informed me of two [new] pupils and arranged the fees himself – in recognition of the situation. (I

would not have managed this.) But when the wealthiest pupils suffer financial collapse, {7} You see how difficult life has become even for me, as it is for nearly all musicians wherever one looks. The path to recovery, artistic as well as material, can lead only by way of my theory; but precisely this is something people find as difficult as the masterworks themselves. Dr. Jonas's book 6 will now be published in the fall. Professor Oppel in Leipzig – he has been made Captain, with the Iron Cross! – leads a national-socialist "cell," in which he continues to teach Schenker, now as before, insofar as this is possible. 8 {8} Did Furtwängler answer your letter? 9 Well, that is how things are. Warmest wishes and greetings from the two of us to you both. Yours, [signed:] H. Schenker May 14, 1933 © Translation William Drabkin, 2008 |

|

Alles im Briefe= OJ 9/34, [37], Ausführungen, Bekenntnis zeigt ein ungewöhnliches Maß von Können u. Charakter, wie es nur ganz wenige mit Ihnen heute teilen. Sagte ich, schrieb ich Ihnen das schon öfter, so wiederhole ich auch noch dieses: wenn Jemand, wie Sie, solchen Grad von „Abhorchen“ u. Darstellung zeigt, hat sozusagen das Recht auch auf einen gelegentlichen Irrtum: ein Irrtum auf der Base der Wahrheit ist noch immer wertvoller als ein Irrtum auf einer Base, die selber ein Irrtum ist. Wie leicht könnte es Ihnen widerfahren, was auch mir so oft widerfahren ist, daß Sie, nach Monaten, nach Jahren plötzlich den Blick ganz frei bekommen auch für Dinge, die Sie, durch Tumult des Tages, Mißstimmung, Hast (!), abgezogen zunächst wenig beachtet haben. Übrigens ist die Frage Ą oder Ć, Ć oder ĉ, u dgl. ĉ oder Ą eben die Tonraum-Frage, ob 3, ob 5, ob 8, die zu enscheiden wohl als Schwierigste gelten mag. Nun zur Sache: 1) Der strenge Satz (vgl. II1

, 2. u. 3. Gattung) lehrt, daß die

Nbn genau so frei eintritt, wie der Bruder

Durchgang

2) Dazu kommt eine Unwägbarkeit:

3) Über die Auskomp. T. 5–8 s. „Erläuterungen“, Jb I 203, fig 4 c, die letzten 3

Beispiele,

3

u. Tw.

2

Moz.

Son. am. letzter

Satz, T. 5–8,

4

usw. Der zur der einer solchen Auskomp. zugeteilte Baß Kp. dient

nur ihr

†

, gleichviel ob er auf den „kons. Dg“ von

oben (Sext) oder von unten (Terz) zugeht. Also ist es unstatthaft,

{3} so zu lesen:

4) Es geht nicht an, aus der Auskomp:

5) T. 21–22 bringen eine Abkürzung von T. 5–8

{4} Endlich zu Ihrem schönen dritten Blatt! Das geschichtliche Verdienst Hitlers, den Marxismus aus zugerotte nt zu haben, wird die Nachwelt (einschließlich der Franzosen, Engländer, u. all der Nutznießer der Verbrechen an Deutschland) nicht weniger dankbar feiern, als die Großtaten der größten Deutschen! Wäre nur der Musik der Mann geboren, der die Musikmarxisten ähnlich ausrottet: dazu gehörte vor Allem, daß sich die Massen dieser in sich versponnenen Kunst näherten, was aber eine – contradictio [corr] in adjecto ist u. bleiben muß. „Kunst“ und Massen haben nie zusammengehört, werden nie zusammengehören. Woher nun aber die Quantitäten der Musik-„Braunhemden“ nehmen, mit denen es gelingen müsste, die Musikmarxisten hinauszujagen? Die Waffen habe ich bereitsgestellt, aber die Musik, die wahre deutsche der Großen, findet kein Verständnis bei den Massen, die die Waffen tragen sollten. Fast habe ich den Eindruck, als nähmen Sie an, ich sei von dem Weltumlauf unberührt. Ich habe sehr schmerzliche 3 Jahre hinter mir, voll Sorgen um die Kunst, um uns Beide, um die Mitwelt. Die Sorgen haben meinen Körper stark in Mitleidenschaft gezogen u. wiederum ist die {5} Einsamkeit unserer großen Musik die Ursache, weshalb auch ihre Priester mitgerissen werden. Woher sollte den Menschen auch nur Mitleiden kommen, wenn sie wirklichen Musikern begegnen, wenn da sie schon an der Musik keinerlei Interresse empfinden?! Die Priester werden so selber zum Got Opfer der Göttin! Violins’ Lage ist mir, ohne daß er es wußte, von Zeit u. [sic] Zeit durch seine Schwester bekannt gemacht worden, sie erzählte schaudervolle Sachen! Er schwieg, erst jetzt gestand er seine übergroße Nervosität ein. Doch wußte auch seine Schwester sehr wenig, – das Wenige

war erschütternd traurig – so daß ich über seinen Schritt

5

zu urteilen mir versagen muß. Vielleicht war Niemand so fern seiner Lage, wie ich. Was er

Ihnen {6} seinerzeit versprochen, dann, wie ich höre, leider nicht gehalten hat, ist mir bis zur

Stunde verborgen. Auf die Übersiedlung habe ich keinerlei Einfluß genommen, wie hätte ich es dürfen, wenn ich

ihm nicht einmal in seinen ärgsten Nöten beispringen konnte! Er hat mir 2 Schüler angekündigt u. die Honorare

selbst – in Kenntnis der Sachlage – ausgemacht. (Ich hätte es nicht getroffen.) Aber, wenn die reichsten Schüler

finanziell zusammenbrechen, {7} Sie sehen, wie schwer sich auch bei mir das Leben inzwischen gestaltet hat, wie doch bei fast allen Musikern allüberall. Der Weg zur Genesung, der künstlerischen wie materiellen, kann nur über meine Lehre führen, gerade aber diese fällt den Leuten genau so schwer, wie die Meisterwerke selbst. Von Dr Jonas kommt das Buch 6 dann doch im Herbst heraus. Prof. Oppel leitet in Leipzig – er ist Hauptmann mit Eisernem Kreuz gerufen! – eine national-soz. „Zelle“, in der er nach wie fort vor nach Tunlichkeit Schenker weitergibt. 8 {8} Hat Ihnen Furtwängler geantwortet? 9 © Transcription William Drabkin, 2008 |

|

Everything in your letter= OJ 9/34, [37] – your arguments, your declaration – shows an extraordinary measure of capability and character, which very few people today share with you. If I have already told you, written to you that many times, let me also reiterate the following: anyone who, like yourself, has demonstrated such a degree of "attention" and presentation has, so to speak, the right to make an occasional mistake: a mistake made on the basis of the truth is always more valuable than a mistake made on a basis that is itself a mistake. How easily it could befall you, as it so often befalls me, that things to which you had paid too little attention – and had remained concealed by the hectic pace of daily life, by feelings of depression, or by doing things in a rush (!) – all of a sudden become crystal clear. Moreover, the question of Ą or Ć, Ć or ĉ, and the like ĉ or Ą is that very question about tonal space, whether 3 or 5 or 8, that is perhaps the most difficult to decide. Now to the matter itself: 1) Strict counterpoint (see

Counterpoint, vol. 1, chapters on the second and third

species) teaches us that the neighbor note may be introduced just as

easily as her brother, the passing note:

2) To this an imponderable is added:

3) Regarding the elaboration, mm. 5–8, see "Elucidations,"

Yearbook, vol. 1, p. 203,

Fig. 4c, last three illustrations,

3

and Mozart's Sonata in A minor, last movement, mm. 5–8, in

Der Tonwille, vol.

2.

4

The bass

counterpoint assigned to such an elaboration serves only that elaboration

†

, regardless of whether the

"consonant passing tone" is approached from the sixth above or the

third below. Thus the following {3} reading is incorrect:

4) It is not permissible, given the following elaboration:

5) Measures 21–22 represent an abbreviation of measures 5–8

{4} Finally, your beautiful third page! Hitler's historical service, of having got rid of Marxism, is something that posterity (including the French, English, and all those who have profited from transgressing against Germany) will celebrate with no less gratitude than the great deeds of the greatest Germans! If only the man were born to music who would similarly get rid of the musical Marxists; that would require that the masses were more in touch with our intrinsically eccentric art, which is something that, however, is and must remain a contradiction in terms. "Art" and "the masses" have never belonged together and never will belong together. And where would one find the huge numbers of musical "brownshirts" that would be needed to hunt down the musical Marxists? I have prepared the weapons, but the music – the true German music of the greats – finds no understanding among the masses who should bear the weapons. I almost have the impression that you believe I am untouched by the course of the world. I have endured three painful years, full of troubled thoughts for art, for the two of us [myself and my wife], for my friends. These thoughts have affected me physically, and the {5} isolation of our great music is once again the cause, for which reason its priests are dragged along. How can one expect people to feel empathy, if they encounter true musicians, if since they already feel no interest in music in the slightest. The priests will thus themselves become a sacrificial offering to the goddess! I have been informed of Violin's situation from time to time by his sister, without his knowing it; she recounted terrifying things! He was silent, and only now did he admit the extent of his nervous condition. Yet even his sister knew very little – the little that

she knew was distressingly sad – so that I had to refrain from making a judgment about the steps he

took.

5

Perhaps no one was more ignorant of his situation than I

myself. What he promised you, {6} for his part, but then – so I hear – failed to make good, has to

this time been unknown to me. Regarding his move, I exerted no influence whatever; how could I have done so if I

was unable to rush to help him in his hour of greatest need? He informed me of two [new] pupils and arranged the fees himself – in recognition of the situation. (I

would not have managed this.) But when the wealthiest pupils suffer financial collapse, {7} You see how difficult life has become even for me, as it is for nearly all musicians wherever one looks. The path to recovery, artistic as well as material, can lead only by way of my theory; but precisely this is something people find as difficult as the masterworks themselves. Dr. Jonas's book 6 will now be published in the fall. Professor Oppel in Leipzig – he has been made Captain, with the Iron Cross! – leads a national-socialist "cell," in which he continues to teach Schenker, now as before, insofar as this is possible. 8 {8} Did Furtwängler answer your letter? 9 Well, that is how things are. Warmest wishes and greetings from the two of us to you both. Yours, [signed:] H. Schenker May 14, 1933 © Translation William Drabkin, 2008 |

Footnotes1 Writing of this letter is recorded in Schenker's diary at OJ 4/6, p. 3833, May 14, 1933: "An v. Cube (Br.): 8 Seiten über die Ą." ("To von Cube (letter): eight pages about the Ą."). 2 This symbol appears among Schenker's corrections to Cube's original graph, which probably accompanied all four pieces of correspondence between Hamburg and Vienna in May 1933. 3 The "Erläuterungen" ("Elucidations"), preliminary material to Der freie Satz in its definitive form, are published in Der Tonwille 8/9 and 10 (both 1924) and in Das Meisterwerk in der Musik, vols. 1 (1925) and 2 (1926). 4 Schenker is referring to the essay on Mozart's Sonata in A minor, K. 310 in Der Tonwille 2; in that analysis, the supposed consonant passing tone is treated as part of the main harmony, i.e. a tonic. 5 Probably the decision to flee Hamburg, and leave Cube to manage the Schenker-Institut as best he could. 6 Oswald Jonas, Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerkes: eine Einführung in die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers (Vienna: Saturn-Verlag, 1934). 7 It is by no means true that Hans Weisse was out of touch at the time: Schenker received letters from him in February, March and May 1933, and regular reports about Weisse's composing activities and teaching at the Mannes School. The letters of 1933 were, however, critical of Vrieslander's compositions and Schenker's unalloyed praise for them, and this may be why Schenker appears to be repressing them here. 8 Prof. Reinhard Oppel, who had been awarded a chair in music theory for the express purpose of teaching Schenker's theories. 9 Furtwängler did not reply to Cube's request for a reference until the summer of 1934. |

|

Format† Double underlined |